Disclaimer: Article contains spoilers for “Materialists”

A couple of weeks ago, my boyfriend and I caught a showing of Director Celine Song’s recent film Materialists at our local Landmark theater (mourning the days of indie theaters on every block that we most certainly were never alive for). Afterward, we wandered into the bar next door – dim lights, pool tables, sticky surfaces – and slid into our usual post-movie rhythm. Two drinks in, napkins covered in illegible scribbles, we were deep into one of our favorite couple rituals: playing film critic. I was already off on a tangent about whether the main character Lucy is a feminist, while he countered with something about class archetypes in rom-coms (which we both agree this film is not). But somewhere between debating whether Lucy’s final choice was predictable or quietly radical, I couldn’t help but draw lines of comparison between Materialists and Equimundo’s most recent report, State of American Men 2025. The film isn’t just about a woman choosing between two men. It’s about the uneasy state of masculinity in a world where women are outperforming men in so many arenas, yet still feel culturally conditioned to seek a man who can “provide,” even when we no longer need them to. It’s about men and women caught in a liminal space shaped by outdated provider expectations, leaving men to redefine what masculinity even means when the old metrics no longer apply.

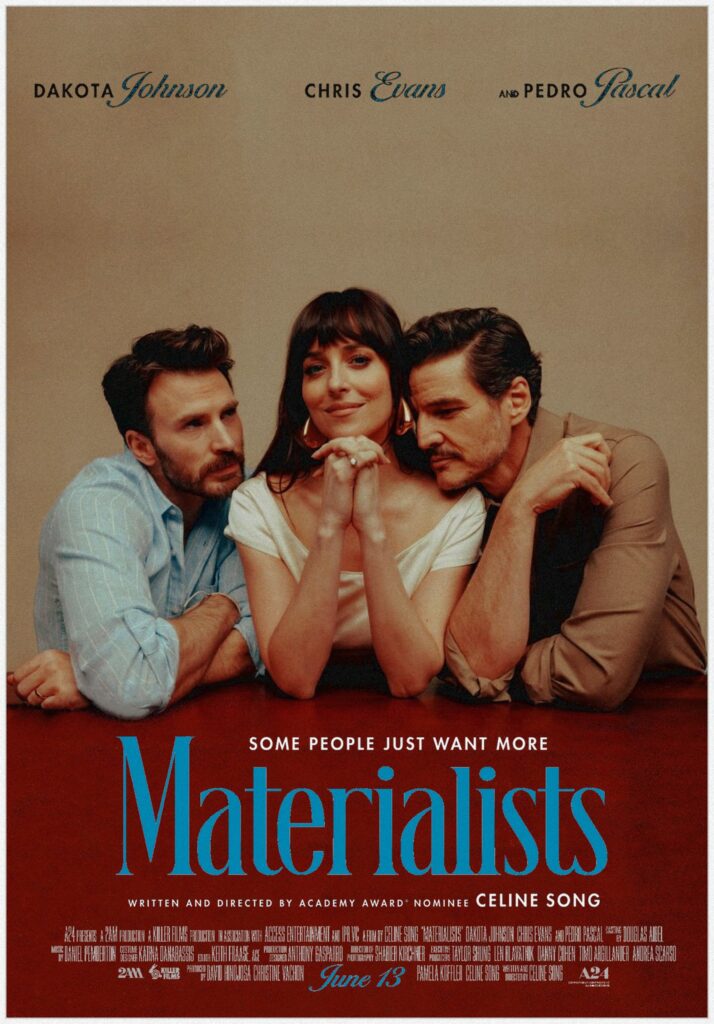

The movie follows Lucy (played by Dakota Johnson), a successful matchmaker working in a New York City dating firm servicing the city’s elite. Through Lucy’s clients’ superficial demands we see the material culture permeating the New York dating scene, with one of her clients proclaiming, “When you said that he’s 47 and only makes $150K a year, I almost said no, but I’m really happy I trusted you.” Other requests her clients make (male and female) are: “6’2″, 5’6″, skinny, fit, fat, white, black, Asian, doctor, lawyer, banker, $100 grand, $200 grand, $300 grand, smoker, non-smoker.” If you think (like I naively do) that dating is about finding love, think again. “Dating takes a lot of effort, a lot of trial and error, a ton of risk, and pain. Love is easy,” states a matter-of-fact Lucy.

Lucy, the self-proclaimed eternal bachelorette, finds herself in a love triangle between uber-wealthy finance guy Harry (played by Pedro Pascal), and her aspiring-actor ex John (played by Chris Evans), both of whom she has chance meetings with at one of her clients’ weddings. Through this triangle, we see Lucy grappling with what she actually wants versus what she’s been taught to want – security, status, the glossy packaging of a “unicorn” – and whether love, in its raw and unpredictable form, can still take precedence over the polished performance of materialism. Both Harry and John depict certain extremes of the impact of societal expectations of masculinity on dating.

I found myself reflecting on the dating struggles I see some of my (heterosexual) friends encounter – expecting men to pay on the first date, even if they make more money than them, and not wanting to date someone who makes less money than they do, even when they are financially self-sufficient. Why, in a post-Jane Austen era, do so many women still view financial wealth as a necessary criteria when it comes to dating?

Equimundo’s report, State of American Men 2025, found that 86% of men and 77% of women surveyed chose “provider” as the top trait that men should have. While we try to expand our sociocultural definitions of masculinity, it is alarming to see how much value and pressure we continue to place on men to be sole providers, when women have proven that we are more than capable of also being financial providers. Breaking against her material proclivities (and those laid out in the report), Lucy chooses broke-but-loveable ex-boyfriend John.

If we want to have a societal fairytale ending, in which the Lucys of the world end up with the Johns of the world, and men are given value outside of being “bread winners,” we must all encourage men and boys early on to see the strength in their roles as sons, fathers, partners, caregivers, friends, and so on. We need men to be active and empathetic caregivers, to talk about their feelings, to ask for help when they need it. All of these traits make us better partners, better parents, better friends – not just men, but all of us. If we want healthier relationships and a more emotionally intelligent society, we have to start redefining what we reward about masculinity. It’s not about lowering expectations for men; it’s about moving them in the right direction. Toward connection, not control. Toward presence, not just provision. That’s the kind of fairytale ending worth rooting for.

For a deeper dive into the data – and for actionable insights on how we can collectively expand what modern masculinity looks like – read and download the full State of American Men 2025 report here.