A mais recente versão do Superman, desta vez dirigida por James Gunn, foi lançada nas plataformas de streaming no fim de semana, então finalmente tive a chance de sentar e assistir. Antes de assistir ao filme, ouvi todo tipo de burburinho online sobre a representação da masculinidade saudável no filme.

O Superman de Gunn acompanha Clark Kent conciliando a vida de repórter do Planeta Diário com um romance inicial com a colega Lois Lane. Ao mesmo tempo, uma controversa intervenção no exterior vira a opinião pública contra seu alter ego de super-herói. Seu inimigo, Lex Luthor, aproveita a oportunidade e orquestra um esquema de tecnologia e mídia que pinta o Superman como uma ameaça global, enquanto o caos meta-humano e extradimensional (e a aparição ocasional de seu cachorro, Kypto) se espalha pela cidade fictícia de Metrópolis. A história se resolve com Superman expondo a manipulação de Luthor e salvando a cidade; Luthor é derrubado, e uma cena nos créditos sugere que os danos que ele causou podem ter consequências ainda por vir.

Então, o que o Superman nos diz sobre o Estado dos Homens AmericanosMinha leitura sincera: Não muito. Superman é um jornalista de origem humilde, mas que, de alguma forma, mora em um arranha-céu de luxo. Uma realidade muito diferente do mercado de trabalho difícil e da recessão iminente que assola a maioria dos americanos. No entanto, o filme me ofereceu um vislumbre de esperança sobre como retratamos a paternidade na grande mídia.

Superman e o Estado dos Homens Americanos

Li muitos artigos, blogs e posts de discussão sobre a representação da masculinidade no último filme do Superman – desde como ele canaliza poder para proteger – e não para representar – o machismo, até se a história enquadra a masculinidade como responsabilidade, ternura com limites, parceria equitativa com Lois e resolução não violenta de problemas. Encontrei pouca coisa que distinga este Superman de versões anteriores ou mesmo de outros super-heróis que exibem características semelhantes. O Homem-Aranha e o Capitão América, por exemplo, funcionam com combustível semelhante: autocontrole, "ajudar o pequeno", responsabilidade após erros e um viés para a desescalada antes da força – o clássico "com grandes poderes vêm grandes responsabilidades". Isso não é uma crítica ao filme em si; ele é limitado em comentários sociais devido às restrições de gênero de ser um filme de super-heróis. Um mito de duas horas não pode suportar o peso das ansiedades de homens reais sobre trabalho, propósito e pertencimento. Se quisermos um instantâneo dessas realidades, precisamos de dados.

O que nossos dados dizem sobre o Estado dos Homens Americanos

A pressão dos provedores é a manchete.

No nosso mais recente relatório bienal, o Estado dos Homens Americanos 2025, descobrimos que 86% dos homens e 77% das mulheres afirmam que "ser provedor" é a principal característica da masculinidade hoje (página 10). É um fardo enorme para carregar, especialmente quando o "Sonho Americano" parece fora de alcance e muitos homens dizem que seus empregos não conferem status ou reputação (página 12). O próprio Superman realiza uma versão idealizada e máxima de provisão – carregando os fardos de todos, o tempo todo. É comovente na tela; é esmagador como uma expectativa diária. É realmente essa a pressão com a qual queremos criar nossos filhos?

A ansiedade econômica afeta fortemente e afeta a saúde mental.

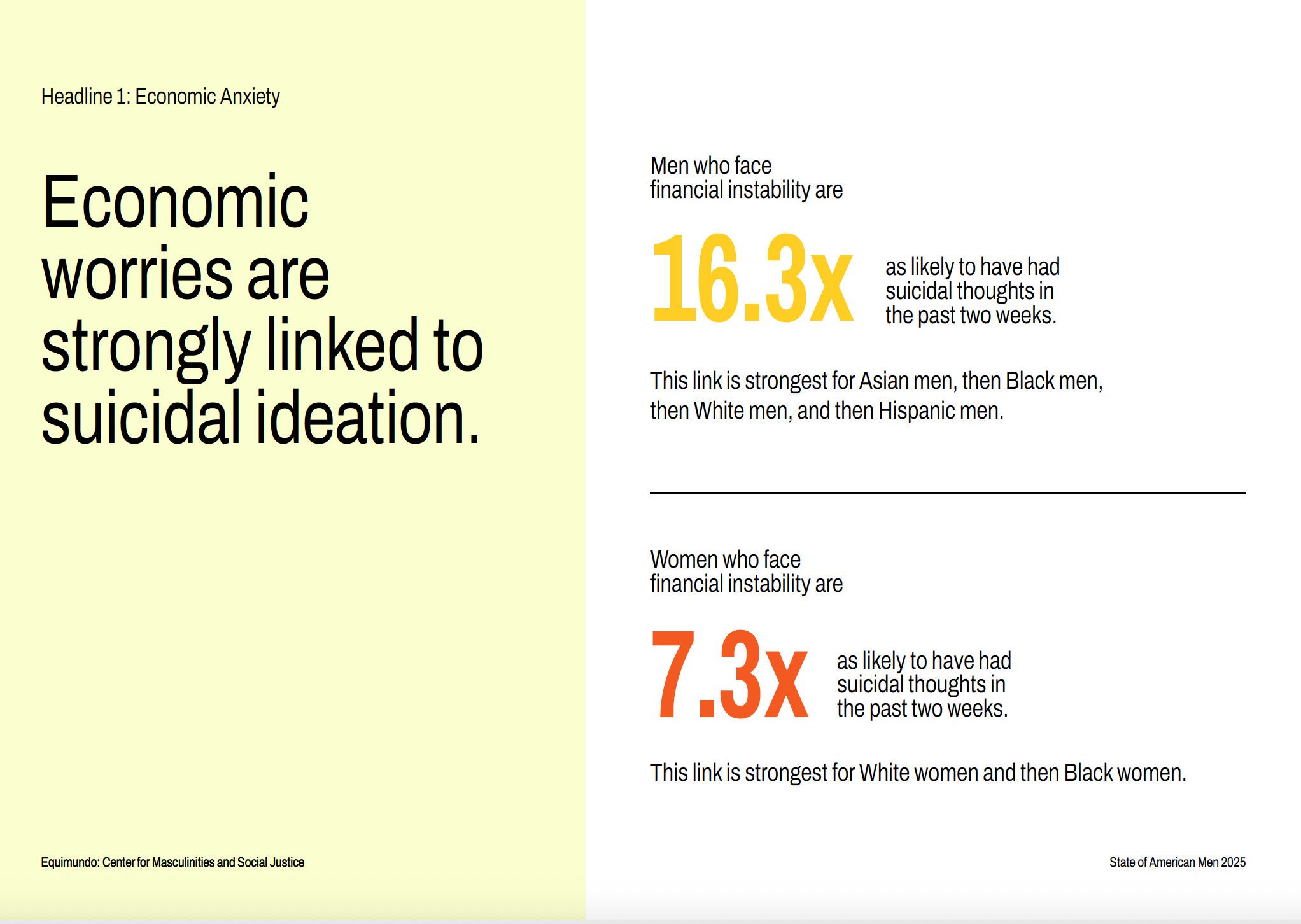

Na tela, Clark parece ter tudo – o emprego dos sonhos, um apartamento iluminado em um arranha-céu em Metrópolis e um relacionamento estável e crescente com Lois. Esse arco claro está a quilômetros de distância do que está causando angústia em muitos homens atualmente. As ansiedades econômicas são muito reais e têm impactos profundos na saúde mental: entre os homens que enfrentam instabilidade financeira, as chances de... pensamentos suicidas salto de 16,3× (para mulheres, 7,3×), com a ligação mais forte entre homens asiáticos, depois negros, brancos e hispânicos. Para homens com mais de 25 anos, estar fora do caminho na carreira está correlacionado a um menor senso de significado e propósito. Em outras palavras, a estabilidade do Superman (carreira, moradia, parceiro, missão clara) está fora do alcance da maioria e não reflete as dificuldades reais que homens e mulheres enfrentarão em 2025.

A masculinidade restritiva está chegando ao fim, e isso é custoso.

O velho roteiro está ficando mais alto: acordo com “Caixa de Homem” as crenças aumentaram desde 2017. Os homens que acreditam na Caixa do Homem são 6,3× mais probabilidade de relatar ideação suicida recente, e homens com alta ansiedade econômica têm 1,8 vezes mais chances de se enquadrar nessa categoria. A maioria dos homens – 63% – afirma que gostaria de ser "mais masculino", especialmente a Geração Z; a ansiedade econômica dobra esse desejo.

É aqui que os limites do filme na discussão sobre masculinidade ficam evidentes: um discurso nobre não vai afrouxar um torno feito de contas, insegurança no emprego e perda de status, mas um modelo diferente de propósito e significado, baseado no cuidado, pode empurrar as normas que fazem esse torno parecer inevitável.

Aqui está o eixo esperançoso: cuidado e paternidade.

Na tela, o centro de gravidade não é a "masculinidade saudável" em abstrato – é o cuidado tornado comum. Jonathan Kent, pai adotivo de Clark, estabelece barreiras (poder como responsabilidade), Martha Kent, torna a compaixão uma rotina (verifique seu vizinho, limpe sua bagunça), e Clark tenta viver esse roteiro em público – dividindo o crédito com Lois, pedindo desculpas quando se excede, apenas dando o seu melhor e aprendendo com seus erros. Essa ética se mapeia para o que vemos fora da tela: o cuidado não apaga as dificuldades, mas ancora o significado. Pais são 1,3× mais probabilidade de relatar um senso de propósito do que homens sem filhos, e o público parece disposto a financiar o tipo de cuidado que os Kents modelam – 61% apoiam licença parental remunerada, 64% apoiam créditos tributários para crianças, 64% apoiam cuidados subsidiados para crianças/idosos. Se apoiarmos o estilo parental dos Kents, o próximo passo é óbvio: construir políticas que permitam que mais famílias estejam presentes – tempo, flexibilidade e cuidados acessíveis.

A fonte não tão secreta do poder do novo Superman: a paternidade cuidadosa

Tire a capa e você terá um garoto que aprendeu – desde cedo – que a força está no serviço e que servir é uma força. O filme de Gunn dá aos Kents uma batida suave mais tarde: um momento na cidade onde Clark cresceu, Smallville, que deixa o Superman de castigo depois do barulho, com seus pais cuidando dele na fazenda. A presença constante de Martha foi tão reconfortante quanto qualquer conversa estimulante. Seu pai não faz discursos, mas sim hábitos: apareça, diga a verdade, faça o trabalho que ninguém vê. Limites também – poder sem restrições não é heroísmo; é ego. E quando Clark erra (porque crianças erram), o pai modela o conserto: peça desculpas, conserte o que puder, tente novamente amanhã.

Martha faz com que isso perdure. Ela é a cadência cotidiana – os check-ins, a caçarola, o "você está se cuidando?" – que mantém toda essa força voltada para as pessoas. (Se você estiver ouvindo, o filme é cheio de batidas domésticas – cuidado silencioso em meio ao espetáculo.)

Esse é o motor do mito. A paternidade cuidadosa ensina ao Superman empatia e propósito. Isso também condiz com o que vemos fora das telas: a paternidade não é um trabalho; é uma prática que dá às crianças um roteiro para o cuidado e dá aos homens e meninos uma razão para usar bem seu poder. Em outras palavras, o Superman não é o Superman, apesar de ser filho de alguém. Ele é o Superman porque, assim como qualquer outro garoto, nasceu para se importar — e também foi cuidado, querido e ensinado a exercitar seus músculos de cuidado.