On October 28, Rio de Janeiro’s state police murdered at least 130 men in two of the city’s favelas. Equimundo stands with activists, politicians, the families of survivors, and all who condemn this violence. This massacre is the latest in a decades-long pattern of police violence in Brazil, overwhelmingly directed at young, Black men.

Equimundo’s work with and on behalf of boys and men originated in Rio de Janeiro in the early 2000s. We partnered with local nongovernmental groups and activists to promote nonviolence – engaging young men in Rio’s favelas in collective protest against police brutality and in amplifying stories of nonviolence and caring manhood that persist despite decades of gang violence and drug trafficking in their communities.

Our research – and the testimonies of young men themselves – shows that gang involvement is rarely a clear-cut matter of being “in” or “out.” Many boys begin on the margins, working as lookouts or couriers. Some go on to become foot soldiers or start selling drugs – often to middle-class buyers who prefer to see themselves as victims of crime, rather than participants in it. A small number of them rise to leadership roles within gangs – but many of them are dead or imprisoned before the age of 30.

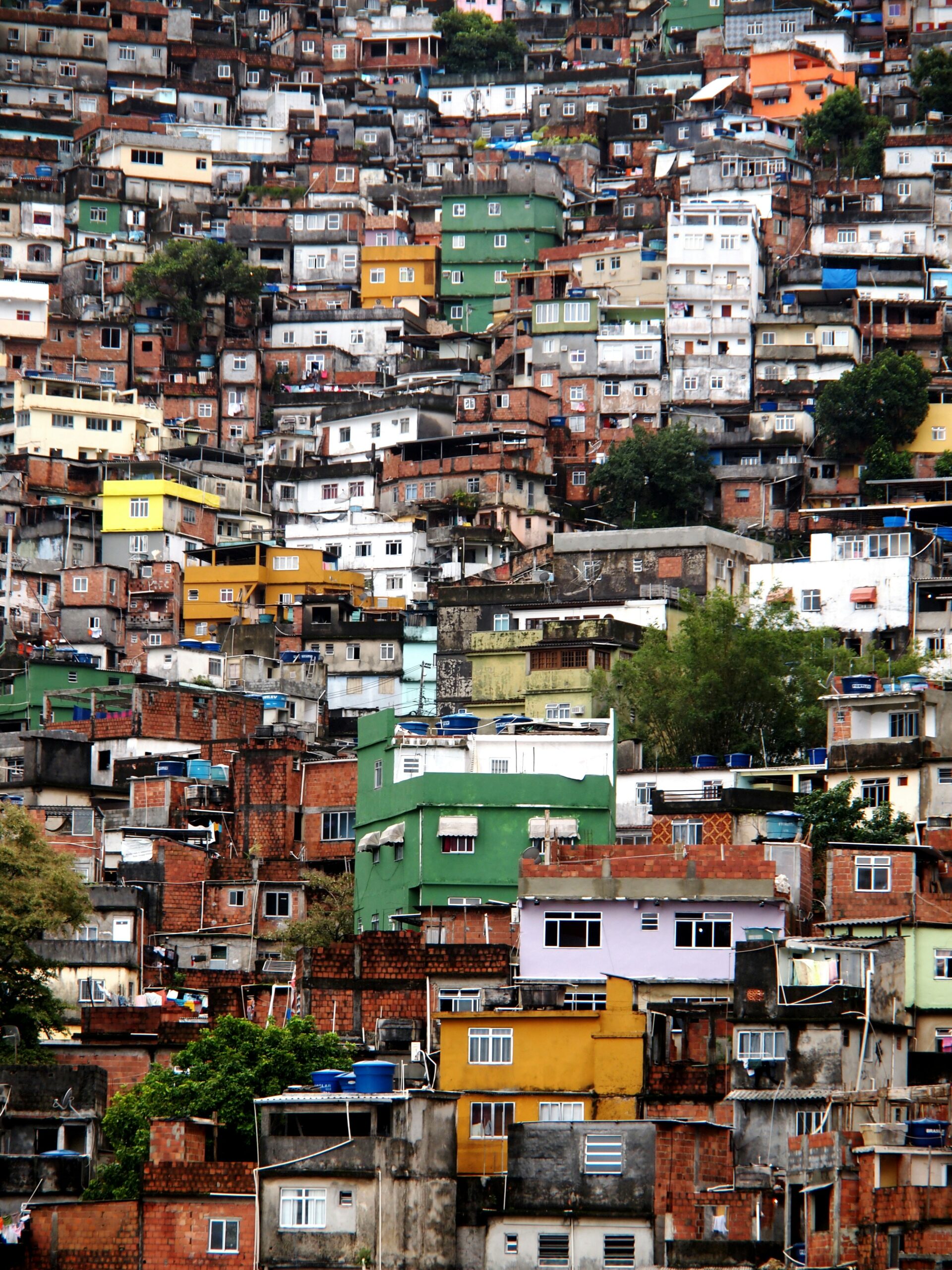

Young men – mostly those of African descent – are too often out of school and out of work, making them easy targets for gangs that rely on a steady supply of labor. Lacking income, status, and a sense of belonging, many turn to gangs in search of economic survival and identity. While a small number create fear and dominate their communities, the vast majority are studying, working, or trying to support their families. Yet police often fail to distinguish between the two – and too often, they don’t even try.

Rio’s state police are deliberately named the Military Police – a legacy of the country’s military dictatorship, which ended more than two decades ago. This nomenclature is intentional. The military framework shapes how the police operate: Gangs are treated as enemies of the state, and the young men associated with them are viewed as combatants – legitimate targets for extermination. Over the years, few officers have been held accountable. Once the killing ends, the state routinely abdicates its responsibilities – failing to investigate and often denying victims even basic dignity.

Jair Bolsonaro came to power in 2018, in part by promoting a tough-on-crime, shoot-first approach. Before that, he had been an ineffective state representative in Rio and an equally undistinguished congressman. As early as 1990, he hosted a radio show where he pushed conservative dogma – including his infamous phrase: o único bandido bom é bandido morto (“The only good thief is a dead thief”). His family record is no less troubling. One of his sons is among the suspects in the assassination of Marielle Franco, and both Bolsonaro and his sons have long been alleged to maintain ties with militias that carry out vigilante justice and extrajudicial killings in favelas – sometimes with funding from local businesses.

Rio’s governor, Cláudio Castro – a Bolsonaro ally who ordered the killings – has argued that the complexity and quantity of weapons justify the action. But what he fails to acknowledge is that the proliferation of weapons in Brazil is partly a result of weakened gun control laws enacted under Bolsonaro. It also reflects the police’s failure to stop the flow of arms – and the government’s chronic inability, or political unwillingness, to improve the quality of life and economic prospects for residents of the favelas.

This massacre is part of a recurring pattern – not just in Brazil, but globally. We see similar cycles of state violence in the United States and in Benjamin Netanyahu’s assault on Palestinians in Gaza. These acts are often tolerated, even justified, in the name of security – creating a dangerous sense of permission for further violence. But this approach does not work. Sending in police to arrest and kill more people will not solve the problem. Only systemic change can address the root causes: investments in education, expanded economic opportunity, and policies to reduce racial and economic inequality – especially for Brazil’s Black population.

The deepest tragedy is the loss of young Black and Brown lives. Every body laid out in the street belonged to a young Black man. Nearly all those called to identify them were women – mothers, sisters, grandmothers, wives, girlfriends. Many will face lifelong grief, poverty, and trauma – with little support from the state that failed to protect them.

In May 2026, Equimundo – together with WOW (Women of the World) and in partnership with Redes da Maré, Instituto Mapear, and Instituto Papo de Homem – will co-organize the MenCare Changemaker Summit, a global event on caring manhood, to be held in Rio de Janeiro. We will bring together policymakers, media, private sector partners, and fellow researchers and activists to build a shared commitment to promoting caring, connected manhood.

We dedicate the MenCare Changemaker Summit to the young men and other victims of Brazil’s police violence – and to those who carry the weight of their absence. We honor all who mourn them, and all who, like us, refuse to accept this violence as normal. We stand with those demanding justice, and commit ourselves to building the systems of care and equity that make such violence impossible.